Birds Whispering Memories

When I sift through old photo boxes passed down from my elders or browse through abandoned photographs at flea markets, the ones that affect me the most are those with notes scribbled on the back. Notes that make the photo speak—capturing lived moments, longings, sorrows, and joys. Perhaps due to my love for collecting, I try not to neglect adding my own notes to my photographs.

In the digital age, the photo box has been replaced by a designated folder on a storage drive, and handwritten notes on the back have been swapped for the metadata we access with a right-click. Future curiosity about dates and technical details is now satisfied automatically by digital cameras, but adding personal notes and descriptions remains at our discretion.

For my bird photographs, I usually note the species’ Turkish name, followed by its italicized Latin name and the location where it was taken. But sometimes, these notes extend into stories that leave a lasting mark. When I revisit these “right-click notes,” I start seeing friendship in the frame of a lone shorebird feeding along an endless beach, or a black stork frozen in time suddenly becomes my most expensive shot. A moment witnessed by a child I met that day turns priceless in an instant.

December 2008, I’m in İğneada with fellow birders. I head out to the field with the team in the morning, but I’m battling a terrible flu. With no remedy in sight, I return to the hotel, hoping rest will cure me. Within minutes, I drift into a deep sleep, likely to spend the entire day in bed.

Fikret Can, the elder brother of our team, calls: “Son, how are you?” He tells me about the sanderling and says he’s coming to pick me up. Is it the bird I’ll be seeing for the first time that heals me, or is it this wonderful person who cares so much for his team? I still wonder, but at that moment, I start to feel better.

For him, just seeing a beautiful bird, observing it well, and capturing a great photograph isn’t enough. While doing all this, Fikret also makes sure that everyone in the team gets to see this charming creature. That sanderling becomes a collection of images with a deep story of friendship. Every time I look at it, I will drift into its beauty and remember the wonderful people.

I'm in Ordu for work. The Melet Delta is a crucial stopover for migrating birds. You never know what species you might come across. I’ve asked my local contacts to keep an eye out, and they call me whenever they spot something unusual.

Meanwhile, the office is buzzing—discussions about organizing that year’s hazelnut harvest are in full swing. My habit of answering incoming calls isn’t exactly winning me any favors. And when I start asking questions like, “Is the bird white?” or “How big is it?”—well, let’s just say the frowns deepen.

“Brother, a bird just landed—tall bird, white, but with yellow on its neck. It’s fishing at Melet.”

“I have an important loan matter to handle at the bank. Let’s continue the meeting later,” I announce, while discreetly grabbing my camera bag. Not sure how convincing that excuse is, but under skeptical gazes, I slip out of the office.

Straight to the Melet River…

About 10-15 meters from the shore, a Eurasian Spoonbill is fishing, generously granting me one of the easiest "loans" I’ve ever received.

After an unproductive day, in the final moments of light, nature grants us a brief but breathtaking spectacle at a pond along our return route. Leaning across the backseat of the car toward the window on the other side, I start pressing the shutter.

I don’t even realize that the object I’m using for support is a Canon Mark III with a 600mm lens belonging to one of my teammates—and that they’re desperately trying to pull it out from under me.

A 40D, a Mark III, two 600mm lenses… The most expensive setup I’ve ever used to take a photo. A Black Stork.

One of the hardest things about bird photography is that, while focusing on capturing a valuable species, you sometimes fail to see the world around you with the creative freedom photography requires.

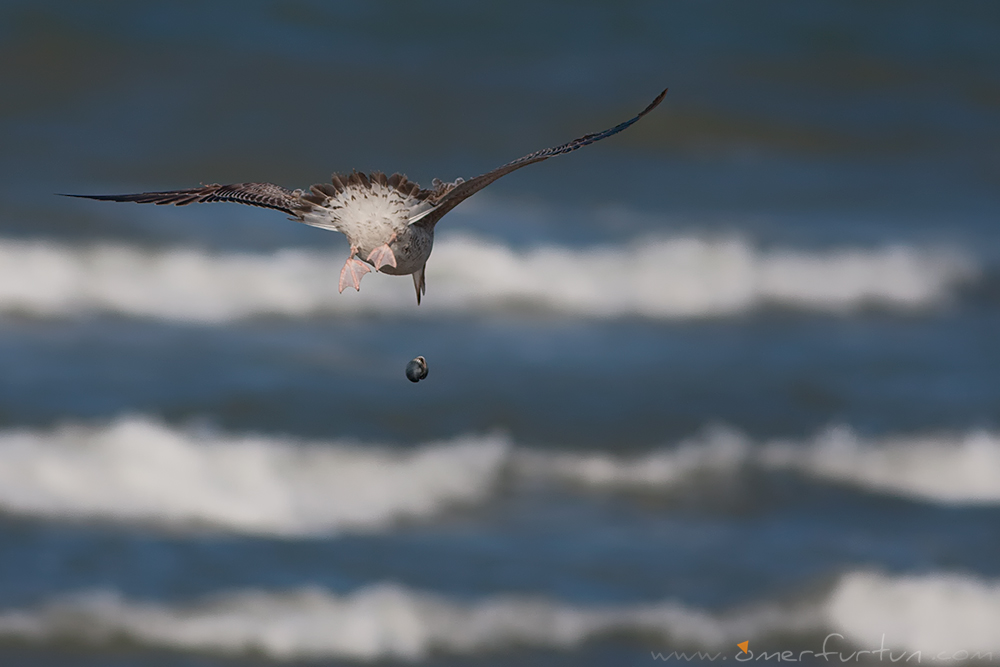

This particular photo reminds me of 12-year-old Murat, who had come out for some fresh air with his mother in a wheelchair. At that moment, I was fully immersed in photographing a great crested grebe, believing it to be the most worthy subject in the area. But Murat was the one who made me pause.

“Abi, look! That seagull is posing beautifully,” he said.

The photo that now hangs in Murat’s room, which he titled “Play Freely,” is, without a doubt, the most valuable photo I’ve ever taken.

Not every shot carries a beautiful memory or story, of course. This crested cuckoo photo is one of those I have little enthusiasm for—whether it’s viewing, sharing on photography sites, or receiving comments. A shot of a bird that seems to cry out from a day when I believe I disrupted the ethical values of nature photography…

To get closer to this Grey-headed Swamphen, I observed its every movement for five days, waiting for hours for the iridescent feathers to catch the perfect light in the ideal position. We spent so much time together that I could recognize it if I saw it again.

On the last day, it finally stopped on the mound where it would climb daily but never pause long enough for a single shot, as if saying, "Go ahead, take your picture." From that, I gathered that it recognized and maybe even liked me. Then again, maybe it chose this way just to avoid spending a sixth day with me.

Under the guidance of fellow birdwatchers, visiting Denizli is like stepping into paradise for bird photographers. The water’s edge resembles the studios set up at photography fairs for testing equipment. In these natural studios, the models work hard to give their best poses—sometimes standing proudly alone, sometimes playing and splashing around with their friends. There is no assigned role, but as one species leaves, another arrives.

You can recognize a photo taken in Denizli without even looking at the description. The more you watch, the stronger the urge to be there grows. Just as you can’t truly be a Fenerbahçe player without scoring against Galatasaray, you can’t truly be a bird photographer without taking photos by the waters of Denizli.

This photo of a Red-footed Falcon, unwilling to share its prey with anyone, reminds me of my teammate who loves to share—my brother Ulaş, who let me share in the joy of observing that moment.

Sometimes, moments freeze in frames, allowing everyone to write their own story beneath them—moments where what the photo makes you think about is more enjoyable than any notes attached to it.

For now, it’s a blank frame with nothing more than the species name and location. Who knows? Maybe one day, this singing European Robin from Ordu, will inspire someone to write songs and compose melodies for him.

Wishing for beautiful days when conflict photos remain only in memories, with messages of peace written upon them… Don't forget to leave notes on your photos.